|

||||||

|

New Canadian Museum Has a Battlefield Focus |

||||||

|

by CLIFFORD KRAUSS April 27, 2005 OTTAWA - This may seem an odd time for Canada to build a museum devoted to war. Its per capita military spending has dipped so low in recent years that to transport aid to the victims of the tsunami that swept over South Asia in December, its armed forces had to rent heavy-lift aircraft from Russia. But on May 8, the 60th anniversary of V-E Day, the Canadian War Museum, which has been around in one form or another since 1880, will officially open the doors to its grand new home and a greatly expanded collection: military artifacts that span the ages from early conflicts among indigenous peoples to Canadian participation in recent peacekeeping operations in the Balkans and Afghanistan. As the most ambitious architectural project in this reserved Victorian capital in nearly 20 years - and one designed, it just so happens, by a Japanese-Canadian interned during World War II - it is a deeply evocative museum that honors the country's fallen soldiers but also warns of the horrors of battle. The exhibits have the normal accouterments of any war museum: vintage jeeps and tanks, war planes suspended from the ceiling, along with one of Hitler's limousines and the obligatory collection of medals for valor. But there will also be portrait paintings of a war bride and a shell-shocked soldier, an audio re-creation of the writings of a Loyalist child refugee escaping the American Revolution, and a teddy bear once carried by a Canadian Army stretcher bearer killed in World War I, given to him by his daughter as a good-luck charm. And there will be special spaces for spiritual reflection. There is nothing bellicose about the exhibits, and there is little if any glorification of battles or generals. But this is not a pacifist museum, either. Amid the audio, texts, battle models and maps, it is about telling the stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary things during extraordinary times - often in an effort to build a country out of a frigid wilderness, and eventually to fight dictatorships and protect democracy. "The basic message of this museum is that we wish to tell Canada's story of military history in all its personal, national and international dimensions," said Joe Geurts, chief executive of the museum. "But the other message is that war is a devastating human experience." Canada has sharply cut its military budget over the last 15 years and allowed its armed forces to fly in 40-year-old helicopters. Military officials hope the museum will reawaken memories of battles like Vimy Ridge, fought in northern France in 1917, that helped forge a Canadian identity independent from the British motherland and a pride in a Canadian military that by the end of World War II was the fourth-largest in the world.

The directors of the Canadian War Museum insist that Mr. Moriyama's personal history had nothing to do with his selection, and Mr. Moriyama resists even talking about an episode he says was painful. But Mr. Moriyama's life experience - that of an innocent boy caught up in an injustice of war who nevertheless grew up to embrace the Canadian ideals of fairness and inclusiveness - is a neat metaphorical match to the message of regeneration that permeates the building's design and landscaping as well as its permanent exhibition. "It's a bit of an irony, but it's appropriate that we got the job," Mr. Moriyama said matter-of-factly of himself and his partner, the Ottawa-based architect Alex Rankin, who grew up in strife-torn Belfast. Mr. Rankin said the building attempts to be "quiet, modest, yet strong - a degree of what it means to be a Canadian." He continued, "A word that is not there is glory." The museum has already won enthusiastic accolades from Canadian architectural critics, who have called it a breakthrough building that promises to revitalize the city's Ottawa River waterfront, west of Parliament Hill. Occupying 450,000 square feet, the museum is a low-lying building that appears to hug the land. Its arching roof is designed to sprout with high wild grass and flowers; it provides an easy walkway over the building with long, gentle ramps coming up the facades between a meadow on one side of the museum and the river on the other. Taken as a whole, the building looks like a bunker, but one that appears to be at peace with nature long after a battle is over. The interior's concrete walls slant in different directions, giving a sensation of strain and instability, but the structure does not divert attention from the drama of the exhibits. There are several rooms dedicated to spiritual healing and reconciliation. A series of displays covering centuries of battles leads into the chapel-like Regeneration Hall, a high-ceilinged space whose angular window frames the monumental Peace Tower atop Parliament Hill. The stark Memorial Hall contains a single artifact: the headstone that marked the original resting place, in a French cemetery near Vimy Ridge, of the Canadian Unknown Soldier. Through an aperture above the chamber, a ray of sunshine can strike the tombstone once a year at precisely 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, Canada's veteran's day, known as Remembrance Day, marking the end of World War I. The exhibits incorporate audiovisual effects to convey some of the sounds and the feel of the battlefield, and to offer an interactive complement to the numerous historical texts, artifacts and models. Visitors will walk between video firing lines of opposing French and British soldiers during the Battle of Quebec of 1759 amid the sounds of musket fire, screams and the music of fifes and drums. They can explore the model of a World War I trench, with flashes of artillery and machine gun fire appearing in the skyline above the lip of the ditch. And they can walk up the metal ramp onto a World War II infantry landing craft to watch archival film of the D-Day Normandy landing. The sounds of the sea and soldiers talking to one another are replaced gradually by the building of artillery fire in the distance, and finally by a barrage of machine gun fire and ricochets as the ramp opens to the beachhead. One video display will take visitors to an observation post in the Korean War. There will be the sound of ruffling clothes and breathing before a twig snaps and a flare is fired over a valley, revealing a huge Chinese frontal assault, with automatic weapons ablaze. "War is organized violence, and we don't want to gloss that over," said Dean Oliver, the museum's chief curator. The $100 million project was approved five years ago by Jean Chrétien, who was prime minister at the time, even while he was cutting military spending. Mr. Chétien was looking to construct a grand building to enhance Ottawa "as more than a place where politics are done," said Senator Jim Munson, Mr. Chrétien's former communications director, and the old military museum was increasingly dilapidated. Meanwhile, with so many World War II veterans passing into their final years, veterans were pressing for a fitting celebration of the 60th anniversary of V-E Day. There were critics who wanted the museum to be named for peace and not for war, in keeping with their sense that Canada should be dedicated to nonviolence. But the Canadian War Museum name was preserved. "The simple fact is that this is a museum about war and its consequences," retired Gen. Paul Manson, a former chief of the Canadian Defense Staff who has been intimately involved in the planning of the museum, said in a speech about the museum at a recent luncheon here. "Canadians need not be ashamed of their involvement in armed conflict over the centuries." |

||||||

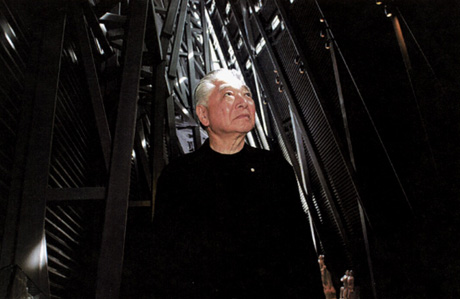

The primary architect of the project is not a former soldier but a victim of Canadian war policy himself. Raymond Moriyama, who at 75 is one of Canada's most respected architects, spent several of his formative years in an internment camp along with thousands of other Japanese-Canadians who, like their counterparts the United States, were confined as possible enemy aliens during World War II.

The primary architect of the project is not a former soldier but a victim of Canadian war policy himself. Raymond Moriyama, who at 75 is one of Canada's most respected architects, spent several of his formative years in an internment camp along with thousands of other Japanese-Canadians who, like their counterparts the United States, were confined as possible enemy aliens during World War II.