|

||||||

|

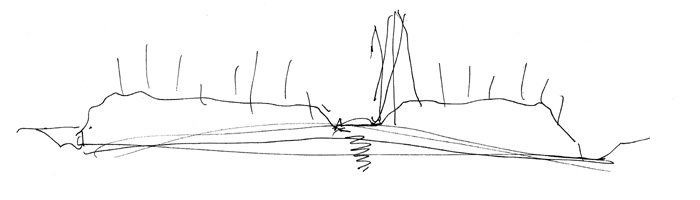

The Sounds of War: How Raymond Moriyama's 'sound' sketch became the soul of the new war museum |

||||||

|

by PAUL GESSELL May 1, 2005

This drawing by Toronto architect Raymond Moriyama was the scribbling that led to an architectural plan for the new Canadian War Museum on LeBreton Flats. In truth, it's the sketch of a "sound" that has been reverberating in Moriyama's head, like the spoken words of a mystical haiku, since the Second World War. The sketch appeared in a recent newspaper advertisement for Moriyama's firm and other key players in the museum's construction. Those who saw the ad would know there was some link to the new museum. But beyond that, the sketch was a mystery. To understand this sketch, one has to travel back to when the 75-year-old, Canadian-born Moriyama was a child living with his mother in an internment camp for Japanese-Canadians in the British Columbia interior. The camp was called Bayfarm. It was deep in the Rocky Mountains near Slocan, along the Slocan River. The Moriyama family had been uprooted from Vancouver simply because of their Japanese ancestry. At age 12, Raymond decided to build himself a secret tree house in the camp. He clandestinely scrounged lumber and a few tools. From the ground, the tree house was invisible even to the Mounties. In the evenings, Raymond would retreat to his sanctuary and listen to nature. He would also imagine the sounds of battle from the war that had engulfed much of the globe. The sounds, real and imagined, blended into one. It echoed in Raymond's head for the rest of his life. This sound is the soul of the new war museum. There are two mounds in the sketch, one representing the museum, the other an attempt to blend the museum into the Gatineau Hills to the north. Stand at the intersection of Booth and Albert streets. Look northward. Straight ahead is the museum. Look a little to the left and you see a hill from the Gatineau range, mirroring the shape of the museum. Just like in the sketch. Approach the museum from the west and, at certain angles, it is as invisible as Raymond's tree house because the river parkland seamlessly rises to become part of the museum's grass-covered roof. You can walk right onto the roof and almost into the third-floor office of its director, Joe Geurts. On the east side of the museum, the roof rises tower-like to a height of 24.5 metres, angling oddly toward the Peace Tower. This part of the roof is covered in copper, just like the Parliament Buildings. Think of this "tower" as Moriyama's tree house. Called Regeneration Hall, this "tower" contains some of our most prized war art, including the plaster maquettes for the sculptures at the Vimy Memorial in France to Canada's First World War dead. Throughout the museum, the walls, roof and floor are built at irregular angles, just like the tree house. But, at $136 million, the museum is far more pricey. This story about long-gone sounds and tree houses might seem just a little too precious to be true. Only people who do not know Moriyama would say that. During construction of Regeneration Hall, the wind howled through the incomplete structure. Moriyama ordered museum officials to tape that sound, which has since become a soundscape played endlessly in the building. "Most architects design something you see but a lot of this museum is based on sound," Moriyama said in a recent Citizen interview. Moriyama inherits his poetic nature from his father. When Raymond graduated from high school, his father handed him an envelope. Raymond was hoping for a cheque. Instead, he got a short poem. "Into God's temple of eternity, drive a nail of gold," the poem said. For most of us, father's advice on graduation day was simply, "Don't drink too much." No wonder Moriyama is not like the rest of us. He has spent a lifetime trying to drive nails of gold into architecture from Toronto's Ontario Science Centre and Bata Shoe Museum to the Canadian embassy in Tokyo and the National Museum in Saudi Arabia. An example of the poetical nature inherited by Moriyama is the party he threw Dec. 28, 2001 in a Toronto restaurant to celebrate knowing his wife Sachi for 70 years. They met when she was two and one-half months and he was two years old. They have five children and 10 grandchildren. Raymond calls Sachi "a peach." Another example of Moriyama's poetic nature involves the official May 8 opening ceremonies of the museum. Prime Minister Paul Martin will be there, along with hundreds, if not thousands, of veterans. It is to be a grand party. But Moriyama has confessed he would rather prolong a planned trip to Peru where, after communing with the ancient mountaintop city of Machu Pichu, he wants to build homes for poor people in shanty towns. The museum is already old hat to Moriyama. He says he walked through it "hundreds of times" two years ago in his mind. He knows it as intimately as the body of a lover. He claims he can spot a one-quarter-inch mistake by construction crews. In the end, the miracle is not that this museum got built after decades of wrangling by politicians, bureaucrats and veterans but that it is not floating in the sky somewhere over a northern forest while an opera, in perpetual concert, performs to the howl of the wind. Ottawa architect Alex Rankin should probably get the credit for adding a dose of reality. He talks of architecture being a combination of pragmatism and idealism. His firm, Griffiths Rankin Cook Architects partnered with the senior company, Moriyama and Teshima Architects, to oversee the structure. Think of Rankin and Moriyama as the ying and yang of the museum. Rankin is the tweedy, barrel-chested architect who came to Canada in 1965 from Northern Ireland. He looks like he could have single-handedly poured the 32,000 cubic metres of concrete weighing 80,000 tonnes that anchor the museum to bedrock. Moriyama is the slight man dressed totally in silky black. He is a brushstroke of calligraphy constantly straining to take flight. So, what has this twosome wrought? Moriyama, as the main designer, was guided by more than memories of sound and poetry. He participated in focus groups before drafting plans. A woman -- he thinks she may have been in Calgary -- said war was a descent into hell that eventually leads to resurrection of the soul. Moriyama was so transfixed by her comment he wanted the entrance of the museum to lead visitors downward, into that metaphorical hell. The bedrock prevented that so, instead, he constructed a roof that slopes downward in the foyer to give one a sense of "compression," a feeling like the world is closing in. Moriyama was also guided by comments of Jack Granatstein, the military historian who was a former war museum director. Granatstein said a museum should tell the story of ordinary Canadians doing extraordinary things in extraordinary circumstances. And that is what we got -- a museum filled with exhibits more about how ordinary Canadians, rather than the generals, coped with war and maintained peace. The resulting structure is 40,860 square metres of glass and concrete sitting on a footprint of 19,000 square metres, and located on 7.5 hectares of land that was once the heart of industrial Ottawa but was razed and left vacant for decades. Moriyama is the first to admit the building, at least on the outside, is not "flashy." Architecture, he says, should be the moon, not the sun. In other words, buildings should reflect glory, not attempt to be the centre of attention. A commons to the south of the building is destined to become Ottawa's new festival plaza. On the north side of the building is Chaudiere Falls and a series of heritage industrial buildings expected eventually to become a trendy tourist area. To prevent the museum from becoming a wall between these public spaces, the architects had to design a building that would allow pedestrian traffic to move through it, even when the museum was closed. The building will, thus, become the hub of more than just museum-related activities. Inside, many features speak of war and peace. There is a meditation area where, at 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, sunlight penetrates a window to shine on the gravestone of the unknown soldier. There are the windows, spelling out in Morse Code, in English and French: Lest We Forget. There is the nine-metre-wide grid pattern used in construction to reflect the nine-metre-wide path required by advancing troops. It is difficult to know whether Moriyama and Rankin got the building they wanted. In public, they say "yes," more or less. They don't always sound convincing. None of their initial 64 proposed designs was accepted by the museum's board. An 11th-hour 65th-compromise design had to be drafted. Meanwhile, bureaucrats from all levels of government interfered. Example: The City of Ottawa decreed northbound motorists will not be able to make a left turn on Booth Street by the museum's main door and parking garage. So, how does one get to the museum from downtown Ottawa, without having to drive to Hull and back? The answer: Check out the secret entrance, way west of Booth, along the Parkway. "Ottawa is a city of bureaucrats," says Moriyama. "I find it more different working in Ottawa than in Toronto or Tokyo or Saudi Arabia. Maybe it's the Canadian way. To penetrate it is a challenge." Moriyama says his building is meant to link Parliament Hill with the more pastoral setting of the Ottawa River parkland. It is also meant to be a catalyst for future development on LeBreton Flats. The overall theme of the building is regeneration, both regeneration after war and the regeneration of the long vacant Flats. Most grand public buildings make a particular statement. When you see the Canadian Museum of Civilization, you see the undulations of natural landscape. The National Gallery of Canada ingenuously echoes both the Parliament Buildings and the nearby Notre Dame Cathedral. What about the "Everybody is going to come up with a different interpretation," says Moriyama. "I personally welcome that. Concrete and copper -- they're just concrete and copper until the individual walks on the floor and finds it's tilted and the walls are tilted. They're going to come up, thematically speaking, with their own conclusion. That's the conclusion I want, not myself as the architect wanting them to like it and feel a certain way."

So, don't feel cheated if you walk into the museum and fail to hear the sounds that passed through a child's tree house 60 years ago. That may be how Moriyama responds to the museum. But it's not the only response.

|

||||||